ittle over a month ago, on October 9, my twins, Talbot and T.J., celebrated their fourth birthdays. In the middle of the party, with plates of cake lying around the kitchen, kids laughing as they chased each other and wrapping paper scattered everywhere, I saw my wife, Kara, from across the room.

When our eyes met, all we could do was smile and shake our heads.

We were both thinking the same thing, that we never thought we’d get to see this. We were hosting a typical birthday party for a four-year-old, filled with laughter and friends and one big mess.

It was … normal.

Four and a half years earlier, we had no idea what every October 9 would look like. We had no idea whether it was going to be a day filled with sadness or one we celebrated as a complete family. We had no idea if our oldest son Tate was going to have a younger brother to play catch with, or if our soon-to-be-born daughter, Talbot, would ever meet her twin.

Because, back in May 2012, we had no idea if T.J. was going to make it.

There are certain memories and specific days that you can never get out of your head no matter how hard you try. I’m talking about everything, including the feelings you had at the time.

The day of Kara’s 18-week sonogram in May 2012 — the day there was a good chance we’d find out the gender of the twins — happens to be one of those uniquely memorable ones for me.

We woke up with an excitement that can only be compared to the joy of waking up on Christmas morning as a kid. The anticipation consumes you, and when it’s finally time to find out, you just can’t control your smile or your heartbeat. It’s incredible. And since we were expecting twins, those emotions were multiplied. Two boys? Two girls? One boy and one girl? It was just awesome.

As my wife’s ob-gyn went over the sonogram with us, Kara and I hung on her every word. So when she stopped talking and looked from the computer down to a piece of paper, we got excited.

Hmmmm. She was writing something down.

We inched closer. Boy? Girl? What is it?

Her pen stopped.

“It looks like the shading seems a bit off with Baby A,” she said.

I glanced up at the blurry black-and-white image on the monitor.

“Really? What do you mean?” I said. I could see the outline of our baby — Baby A — right there.

“This happens a lot,” said the sonographer, turning from the monitor back to Kara. “Don’t worry at all. It could be a variety of things. It could be something, but it could also be nothing. Sometimes this happens when the baby’s heart is abnormal — when the left side is smaller than the right — but it usually happens when the sonograph is captured at the wrong angle.”

We were going to have a baby boy and a baby girl. Kara and I couldn’t stop smiling.

Kara’s shoulders relaxed a bit.

“Whatever you do, don’t get concerned about it right now. You might have to see a specialist and get some further testing, but let’s keep going.”

Hearing the those words from the sonographer gave us some comfort. We weren’t overly concerned — we were still eager to learn the sex of our twins. And we didn’t have to wait long, because just a few moments later, we found out: We were going to have a baby boy and a baby girl. Kara and I couldn’t stop smiling. Our oldest, Tate, was going to have a younger brother and younger sister. It was incredible.

But as excited as we were, Kara and I continued to think about what the doctor had written down on that piece of paper. The moment we left the appointment I reached for my phone and started googling things like left side of heart smaller than the right side and 18-week sonogram. The first result I saw — the very first one — said “life threatening hypoplastic left heart syndrome.” I kept scrolling down. The same thing kept showing up.

I showed Kara. We both said the same thing: “It can’t be this.” There was no way. We said it again: “It can’t be this.” Plus, we weren’t going to make any judgments based on a Google search result. What was the point?

It just can’t be this….

I’m not sure if we were just trying to convince ourselves that everything was fine — that this sort of thing wouldn’t happen to us.

But we were wrong.

A few hours later that same day, we arrived at the Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute in Charlotte for an appointment with a specialist. We expected to hear a reasonable and simple explanation — that the angle of the sonogram had produced some mistake — and then we’d be out of there.

The doctors there performed a fetal ultrasound. The tech finished the exam without much issue and told us that the doctor would be in shortly.

Without surgery, our child would die within a few days of being born.

We heard a knock at the door. The doctor came in. He introduced himself. And then….

“There are some things we need to talk about. Can you follow me down to my office?”

My heart sank. Kara’s did too.

In his office, he sat us down. He didn’t waste much time.

“There’s only one way for me to tell you this,” he said. “This is not easy, but your son is going to be born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.”

I knew those words. They were the same ones that had scrolled across my phone’s screen only a few hours earlier. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome … the very thing we both had said that this couldn’t be.

I looked over at Kara. The doctor kept talking. We were listening for him to say, “But, we can cure it,” or, “We can make it go away.” But the doctor never said those things. He never said anything even close.

“The most likely scenario for your baby,” the doctor continued, “is that he’ll go through a series of three complicated and significant open-heart surgeries.”

Everything was happening so fast. How was this possible?

“The first operation is going to be shortly after he’s born — within the first three days of his life.”

What?

“The next one will be roughly six months into his life.”

I looked over at Kara again. I squeezed her hand.

We weren’t ready for this type of news. At all. But it just kept coming … and it only got worse.

“The third surgery will be when he’s around two years old. And through these surgeries, we’re going to completely reconfigure the way his heart pumps.”

We didn’t know what to think or do. Only a few hours earlier we had received the magnificent news we had been waiting for … and now our baby — who didn’t even have a name yet — was being penciled in for open-heart surgery within the first 72 hours of his life?

Oh, my God.

The doctor told us that the left ventricle in our son’s heart was underdeveloped and too small, which meant he wouldn’t be able to pump enough oxygen-rich blood throughout his body.

Without surgery, our child would die within a few days of being born.

Doctors give your family three options when your unborn baby is diagnosed with HLHS. You can terminate the pregnancy, you can have the baby and refuse treatment, or you can go through with the three surgeries our doctor had told us about.

We were driving to the airport when my phone rang.

There was never any doubt in our minds that we were going to give our child a chance to survive and thrive. So the day after we got the news, we made an appointment to visit some specialists in Boston who had begun performing this relatively new procedure that attempts to improve the function of the left side of the heart. My in-laws were staying with us at the time, and so we all bought tickets to fly to Boston. My parents were living in New Jersey then, and they decided to drive up and meet us. Kara and I needed all the support we could get. So we were stunned when, before we left for Boston, we got help from an unexpected source.

We were driving to the airport when my phone rang. The call was from a number I didn’t recognize. I figured it might be the doctors up in Boston, so I answered.

“Hey, Greg. This is Jerry Richardson.”

Mr. Richardson is the owner of the Carolina Panthers.

“Oh, hi, Mr. Richardson. How are you?”

“Listen, I’m sorry that it took me so long to call you — I just found out about your son. If it’s O.K. with you, would you meet me at my plane this afternoon so I can accompany you to get some answers up in Boston?”

I almost drove the car off the road.

I looked over at Kara and back at my in-laws in the rearview mirror. We all had the same look on our faces. Our eyes were wide-open and our mouths were agape. I had been traded to the Panthers less than a year before, and yet here was this man who, despite not having much of a personal relationship with my family, was willing to sacrifice his time, resources and energy to support us during a hard time in our lives. We were blown away.

“Thank you, Mr. Richardson,” I said. “We would love to join you. Thank you so much.”

Later that day, we flew up to Boston, and the next day we met with some of the leading professionals specializing in neonatal care.

Kara was smiling, giving me this look like, Are you kidding me?

One doctor came into the office and, knowing where we were from, seemed surprised that we had flown all the way up there.

“We’d be happy to take care of your child and your wife,” he told me. “But if you’re asking for my opinion, you have one of the world’s leading centers for pediatric cardiothoracic surgery — and one of the best pediatric doctors in the world — down in Charlotte at Levine Children’s Hospital.”

It was like something out of a movie.

Kara was smiling, giving me this look like, Are you kidding me? I turned back to the doctor.

“Wait … really?”

At that point, we were all laughing. This was huge. We had one of the best pediatric doctors in the world right in our backyard. And as we left the doctor’s office, drove back to the airport and boarded Mr. Richardson’s plane, I thought about the past couple of months of my life.

For as emotionally draining as the previous three days had been, I couldn’t help but think that everything was falling into place. Ten months earlier, Kara and I had been living in Chicago. I was a bit surprised when I was traded, and sad about leaving the Bears. But all I could think of on the flight back to North Carolina was that if I hadn’t been traded we wouldn’t have been so close to one of the few places in the country that could provide the treatment and care that our family needed. It would have been so difficult.

But we didn’t have to worry about that now, because we were going home to Charlotte. And we were going to get some of the best care in the world.

It just so happened that on October 9, 2012 — the day the twins were born — we were on our bye-week. At that point, we felt that everything was truly falling into place. The time off gave the entire family a chance to prepare.

Delivery rooms are hectic. Add T.J.’s condition to the mix and things were amplified. There were a lot of nurses and doctors hovering around Kara. But all things considered, everything went smoothly. T.J. was born at 5:50 p.m., and then Talbot appeared at 5:51.

Before they were born, the doctors had repeatedly asked one thing of Kara: to get the babies up to five pounds. Any lighter than that, and T.J. would be unable to undergo surgery. Things were very tense, but when T.J. came out, you could tell by looking at him that he was heavy enough. And we were relieved to confirm that he was born at seven pounds, five ounces.

But we knew more difficult times were coming.

We were prepared for a lot of things going into surgery. But nothing — nothing — can prepare you for seeing your baby in that condition.

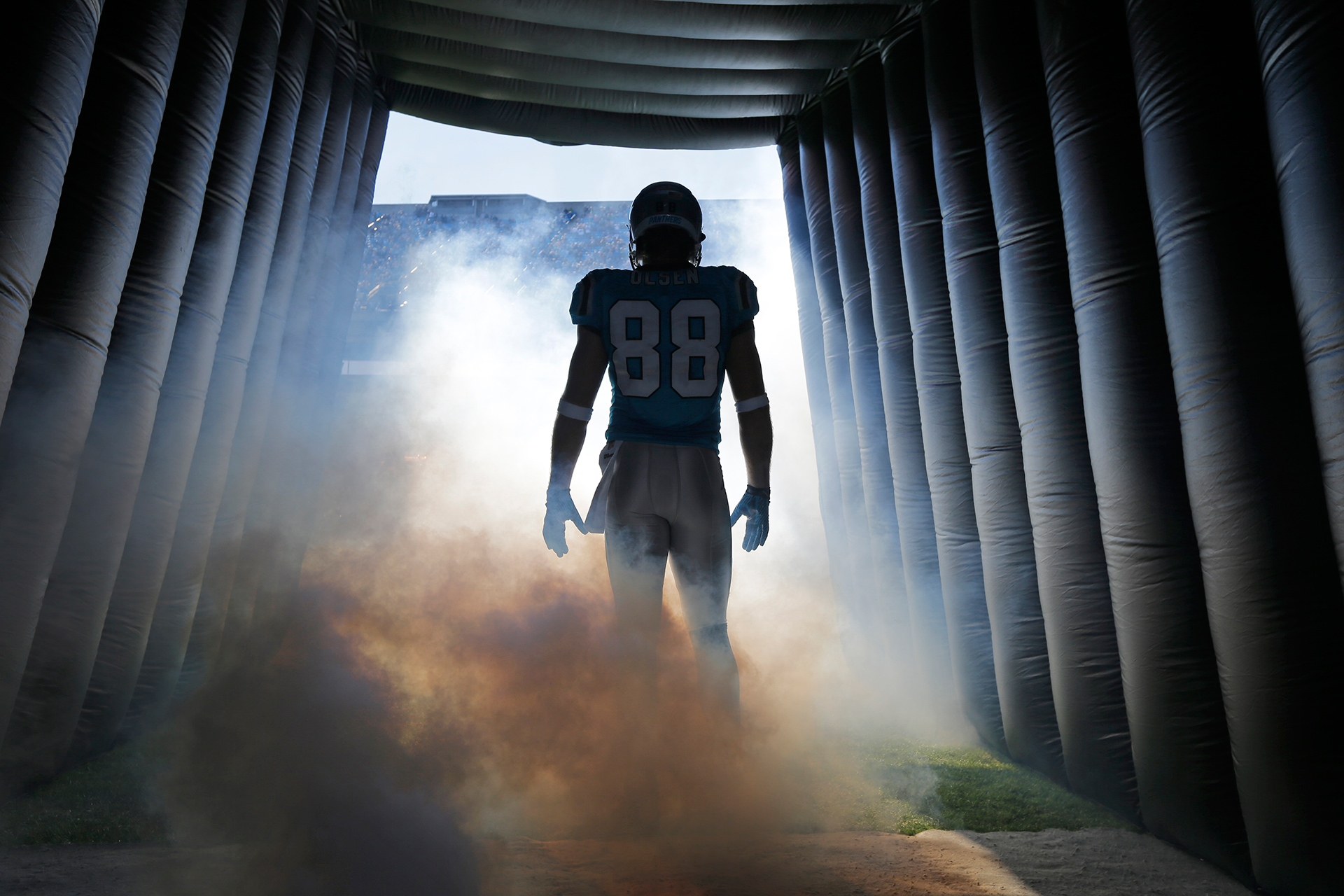

GREG OLSEN

The doctors brought T.J. to the NICU, where they immediately began inserting tubes up his nose and down his throat. He was scheduled to have his first surgery when he was three days old, but because his heart went into rapid sinus arrhythmia only moments after he was born, the doctors opted to perform surgery a day early.

T.J. was in surgery for four hours before the doctor came to see us. I was with Kara and Talbot in their hospital room.

“T.J. is out of surgery and stable. Do you want to come see him?”

Exhale.

I hurried over to the NICU in my scrubs, and when I looked through the viewing window I saw our baby lying there. His chest was still open. Tubes were pumping medicine. Wires were monitoring his condition. We were prepared for a lot of things going into surgery. But nothing — nothing — can prepare you for seeing your baby in that condition. All I wanted to do was give him love.

All I wanted to do was take the pain away.

It was a while before I could hold T.J.

He remained sedated for a couple of days. But soon they were able to close his sternum, which was huge, both from a recovery and a sterility standpoint. After that, the doctors removed the tubes from his body and we could finally pick him up and hold him.

Nationwide, 15% of children born with HLHS pass away during the interstage period.

T.J. stayed in the hospital for the first 36 days of his life before we could bring him home. But when that day finally arrived, we were so excited to get our kids under one roof and have some sort of normalcy in our lives. He had only been home with us for a few days, though, before we realized that we didn’t have the capabilities to adequately take care of him.

During his time in the hospital, T.J. had had around-the-clock medical professionals offering care that Kara and I were not trained to provide. He had to do physical therapy exercises to improve his motor skills. He had to drink a high-calorie formula. He had to eat every three hours. And his vital signs had to constantly be monitored. Sure, we could do those things for T.J., but there was no way that we could do them as well as trained professionals — and the amount of work required was pretty daunting. With the season starting to ramp up, I didn’t want to leave Kara at home to do it all by herself.

That realization was especially important because the time in between the first surgery and the second surgery — which doctors call the interstage period — is absolutely critical to the baby’s long-term well-being. Nationwide, 15% of children born with HLHS pass away during the interstage period. Fifteen percent. That’s a startling number, considering those babies had been healthy enough to make it through the first surgery and be sent home.

We didn’t want to take any chances with our son’s life, so we hired a medical professional to be a part of T.J.’s recovery until it was time for his second surgery.

Over the next four months, T.J.’s nurse lived with us 24/7. At one point, our nurse found that his heart arrhythmia was at a dangerous level, and because of that we had to take T.J. to the hospital. I can promise you that, if we hadn’t had our nurse, we wouldn’t have recognized that T.J. was in trouble. I don’t want to think about what could’ve happened.

And when it came time for him to go into surgery, T.J. showed no signs of setbacks. He was in the hospital for only five days after that second operation, which was a drastic improvement from his first surgery.

Kara and I are convinced that this was a direct result of the extra care.

After talking with other families affected by HLHS, we realized that we weren’t the only ones who felt incapable of providing for our baby’s needs. So when everything settled down after the surgery, Kara and I decided to use our platform to try to help provide some hope and stability to the HLHS community. We started by asking a simple question: What if we could ensure that all families whose children were suffering from HLHS at Levine Children’s Hospital were able to hire a live-in nurse without having to worry about cost?

After a ton of meetings with hospital administrators and doctors, Kara and I launched our foundation, The HEARTest Yard.

If we can support these families on a personal level it can make a lasting difference.

Our main goal was to provide HLHS families at Levine with the same health care options that we’d had. We created a team at the hospital that trains nurses to care for babies with HLHS. Those nurses are then assigned to a specific household and then stay with a family until their baby undergoes its second surgery.

Because extra care can get expensive, we also created a medical benefit that provides these services to families at no charge. Levine doesn’t incur any additional expenses for providing these services, either.

Because of the private benefit that we created, families won’t have to have to pay out-of-pocket costs or worry about dealing with health insurance issues. The hospital won’t have to worry about extra expenses either.

At this point, the medical benefit applies only to cardiac patients at Levine, but we’re hoping to scale this model to extend to each intensive care unit at the hospital.

Being told that your child will be born with HLHS is absolutely heartbreaking. We don’t want parents who are already feeling overwhelmed to have to deal with a big, impersonal, corporate foundation. So while The HEARTest Yard continues to grow at an exciting rate, Kara and I are doing all that we can to ensure that the families we help receive personal attention. When you email or call The HEARTest Yard, you’re going to get someone who can empathize with you.

My thinking is that if we can support these families on a personal level, and help to ensure that they receive the care they need, it can make a lasting difference.

For my wife and I, that type of support came in a number of ways, most notably from our nurse. She essentially became another member of the Olsen household and was able to help us cope with the emotional stress of the interstage period. She really was a hero, and we’ll never forget how she was such a steady, reliable presence during such a troubling time in our lives.

Just looking at him, you’d never know T.J. went through everything that he did.

After his second surgery, T.J. was growing and was relatively healthy. But by August 2014 — when he was almost two years old, and after a number of appointments with the cardiologists at Levine — his heart rate wasn’t where it should have been and his blood saturation levels were low. Because of that, the doctors wanted to get him into surgery sooner than they had originally planned. We thought the third surgery would help to fix his heart arrhythmia, but because of some complications it actually made it worse.

After the surgery, T.J. was experiencing such difficulties that, on Sept. 11, the doctors surgically implanted a pacemaker, which remains there to this day. And for as difficult as the first surgery was — both on our family and on T.J. — the third and fourth ones were also as upsetting since T.J. was older and just starting to speak.

Before and after these surgeries, you could actually see the concern on his face and hear it in his voice. As the doctors rolled our son into and out of surgery, he kept asking, “Where’s Mommy? Where’s Daddy?”

T.J.’s irregular heartbeat gradually normalized, and one day, we received the news that he was in good enough condition to come home. And on Sept. 20, 2014, T.J. was discharged, and we brought him back — for good.

These days, T.J. is in a great place. If he feels certain things or has any abnormal sensations in his chest, he knows that he needs to tell us about them immediately. Every so often, he’ll look at us and say that he has a special heart. He has a very keen sense of who he is.

T.J. is a smart little kid, too. He goes to school and loves learning. He has a ton of friends and plays soccer with them once a week. Just looking at him, you’d never know T.J. went through everything that he did.

If there’s one thing I learned in the last four and a half years, it’s that giving up isn’t worth it.

GREG OLSEN

And, of course, T.J. loves his twin sister, Talbot, and his older brother, Tate.

Every time Kara and I go out at night — whether it’s for the foundation or otherwise — our kids ask if we’re going to go help T.J.’s heart friends. Yes, they call the people at The HEARTest Yard T.J.’s heart friends.

At one point in our lives, we had no idea what every October 9 would be like. When Kara and I looked at each other at Talbot and T.J.’s birthday party, we saw so much happiness. We never could have imagined that life would have taken us down this road. But we know we were put in this position for a reason, and we’re going to do everything we can to help T.J., and to ensure that other families get all the care they need to give their children the best chance at survival.

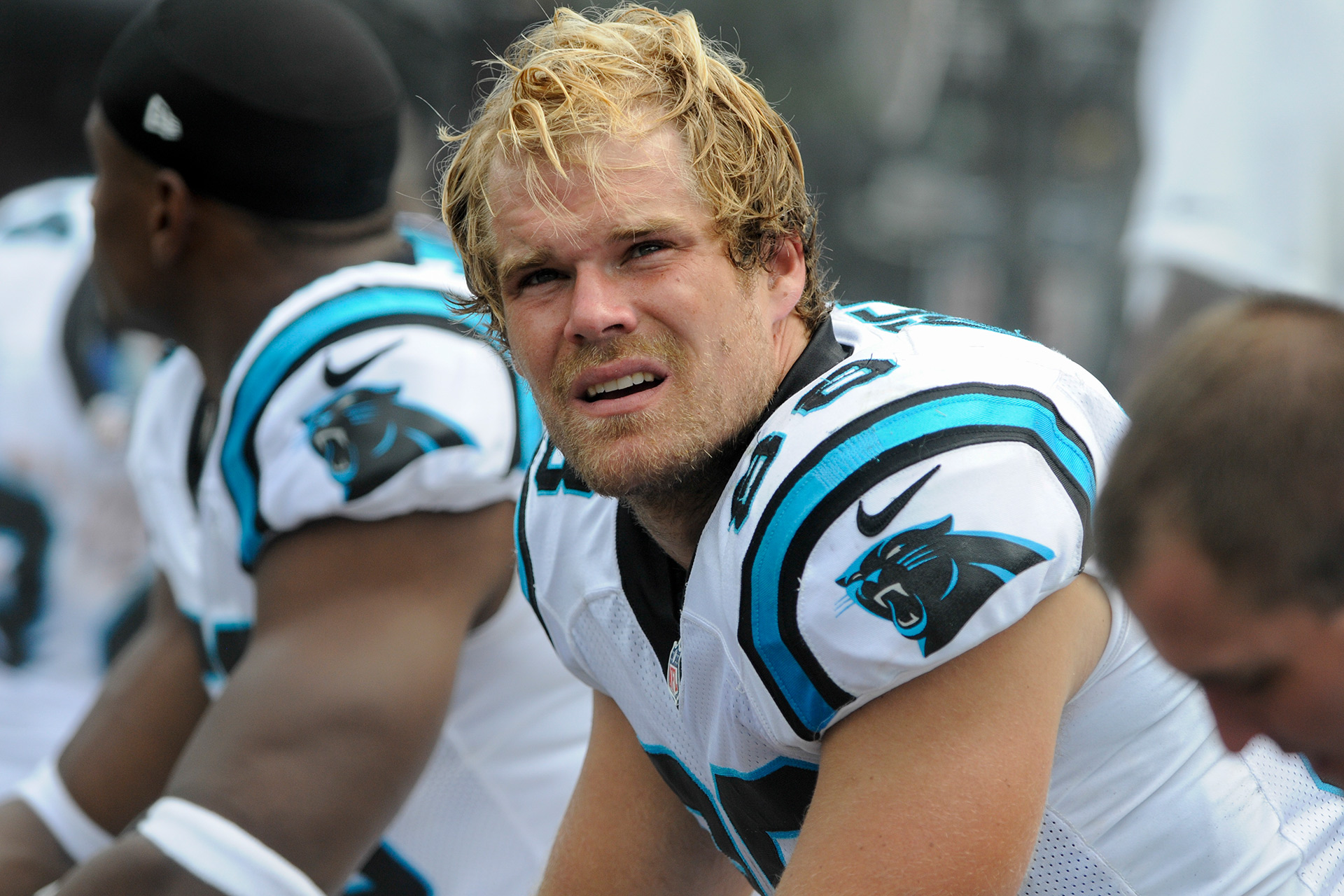

Now, when I take the field on Sundays, I get to look over to the sideline and see my three children throwing popcorn at one another and my beautiful wife waving to me. Whenever I see all four of them together, I take a moment to realize how far we’ve come.

For as much fun as I have out there with my teammates, nothing will ever compare to the joy I get from running around and laughing with my kids. They’re who I live for, and they’re growing up so fast.

And after everything that’s happened to our family, I know they’re going to be able to accomplish anything they want to in life. Because if there’s one thing I learned in the last four and a half years, it’s that giving up isn’t worth it.

T.J. knows that best.

Kara and Greg are founders of The HEARTest Yard. To learn more about the foundation and how you can get involved, visit the website here.